Introduction

At a time when the effects of climate change are becoming increasingly apparent, the world faces the challenge of drastically reducing greenhouse gas emissions. A crucial aspect of this challenge is the regulations governments adopt to make this happen. This article describes how the price of emissions works at the European level, what an emission trading system (ETS) is, and what it all means for the future. Finally, a critical view will be taken and any shortcomings of this system will be formulated.

Pollution problem

We know that the emission of greenhouse gases has detrimental effects on the climate and consequently on fellow human beings. In the past, emitters of greenhouse gases could emit indefinitely without experiencing consequences for the damage they caused to the climate by doing so. To efficiently solve a pollution problem, a government can generally adopt two possible solution strategies: a first option is to introduce a tax on the polluter’s emissions that, in the optimal case, is equal to the damage those emissions would cause. In this way, you make the polluter pay for its damage. A second possibility is to impose a maximum amount of emissions on companies. You can let companies trade among themselves in these emissions, so this second choice also puts a price on emissions. Due to a combination of political and economic reasons, Europe has gone for this second option for the pollution problem of greenhouse gasses [1] [2]

The ETS

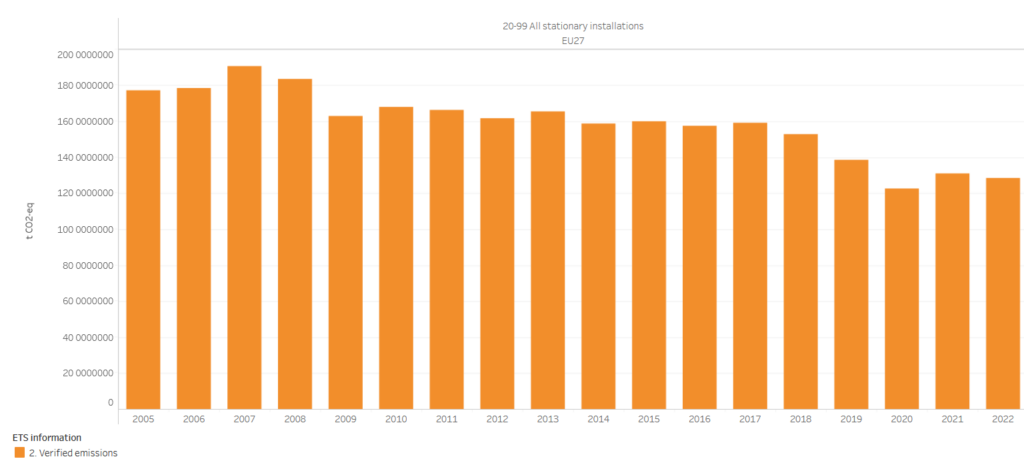

The EU has set a cap on the combined emissions of all companies in the EU’s most carbon-intensive sectors. Since the EU does not know which companies can most easily reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and which can do so at a lower cost, they have created an emissions allowance market. Each year, companies must surrender allowances equal to the amount of greenhouse gases they emitted during that year. This means that although the overall EU emissions are capped, the specific companies responsible for these emissions are determined by the market. The market mechanism ensures that companies having difficulty with decarbonization are required to buy allowances, while those capable of reducing CO2 emissions more easily can do so and sell the excess allowances to others. This gives companies a financial incentive to reduce their emissions but at the same time ensures the reductions are achieved by those who can do it with the least effort and cost.

This cap decreases annually to eventually reach zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2040 [3]. Here we immediately see a reason why the EU has chosen a quantity cap instead of a direct tax: Namely, that the mission of “together towards net zero emissions” likely garners more support than abstract concepts like the economic cost of a ton of CO2 [4]. There are four sectors subject to this ETS system: namely, electricity generation, heavy industry, intra-European aviation and, since 2024, the maritime transport sector [5].

Allocation of emission allowances

Emission allowances from 2005 until about 2013 were allocated mainly for free by “grandfathering”: companies that emitted a lot of CO2 before the start of the system received many emission allowances [6]. Also, industries with higher CO2 intensity received more allowances than their counterparts with lower emissions. This approach should help ensure that this type of tax does not place an excessive burden on companies affected by the measure from now on. The rest of the certificates were then auctioned off with the proceeds going to national governments. Since 2013, a larger portion of the certificates have been auctioned instead of being granted for free. This, along with the price increase of these certificates is a major reason for the huge increase in revenue from this tax.

The waterbed effect

A direct consequence of the mechanism of this system, is the waterbed effect. This means that if one part of the European market makes more effort to reduce their CO2 emissions, emissions are shifted to other companies. You can think of this as water in a waterbed: If you press on one part of the bed, the water will move, but this water does not disappear: it just moves to another part of the bed. So to illustrate, if more people take the train instead of the plane for intra-European transport, this implies no reduction in the total CO2 emissions of the European union. The emission rights that would have been purchased by the airline will now be purchased by another polluter.

However, this reasoning is not entirely correct. To counteract a surplus of allowances, the EU introduced a market stability reserve (MSR) and allowance invalidation rule in 2018 [7] [8] [9] [10]. A detailed description of this legislation would lead us too far, so in summary, it can ensure that emission reductions in one country still lead to EU-wide emission reductions [11]. If we use again the analogy of the waterbed, the EU is puncturing the waterbed with these regulations. So that when you press on the bed, that the water does not just move but escapes.

Critique of the EU ETS

A first criticism of the ETS system is that it would be an additional tax that makes CO2-intensive products more expensive without making life better for the average European citizen. But this certainly need not be the case. The spending of the proceeds obtained from the EU ETS is left to the member states. In Switzerland, for example, revenues from their ETS are distributed back to each citizen in the form of a lump sum of money. Most economists do agree that this is probably suboptimal [12], and that this money is best used to reduce the distortionary effect of taxes such as personal income taxes by lowering them. Also, some of the revenue can be used to compensate the most vulnerable segment of the population for the price increase that will be caused by the ETS.

A second criticism is that the EU ETS is suboptimal in that it applies to some industries and not to others. For example, transport by cars and trucks and CO2 emissions from domestic heating are not covered by ETS. As a result, the property of cost-optimality is lost: more CO2 is not necessarily going to be saved where it is cheapest, thus making CO2 reductions more expensive than necessary. ETS 2 ameliorates this problem by introducing a new ETS that will exist separately from the current EU ETS for these sectors. However, to fix the problem completely, these sectors would also have to be included in the existing EU ETS. When you have two separate systems, you tax one ton of CO2 harder than the other, this means that there will be more than optimal CO2 savings under the system with the high CO2 price and less than optimal savings under the system with the low CO2 price [13].

The last major criticism made of the EU ETS is that it would lead to “carbon leakage”: This means that if a country or region decides to adopt very strict climate regulations that companies will move away from that region to then produce their goods somewhere else. Then they can export these goods from the region with lax regulations back to the region with strict regulations. This is clearly something that should be avoided. In the past this was countered by the free allocation of emission allowances but this measure is being phased out. In the future, the EU will partially counter this by introducing a CBAM (carbon border adjustment mechanism) in 2026 [14] [15]. This means that for countries that are not members of the EU and do not have equivalent regulations, an import tax equal to the carbon tax will be introduced as if the company was located inside the EU. This ensures that companies outside the EU also have to pay CO2 tax if they want to export to the EU, and thus cannot undercut those based in Europe. Furthermore, the revenue from this can be used to promote the competitiveness of European companies or reduce other distorting taxes.

Conclusion

The European ETS is the first major CO2 emissions trading scheme and is at the heart of European climate policy. Never before, nor since, has there been a decision to work together against global warming on such a large scale AND with such ambition. Although the system has not been without shortcomings and is constantly evolving, it has played a central role in the EU’s efforts to reduce emissions. It has done so efficiently, serving as an example to the rest of the world. In conclusion, the EU ETS is the most important climate legislation in the EU and may have been one of the most influential decisions in the world’s fight against climate change.